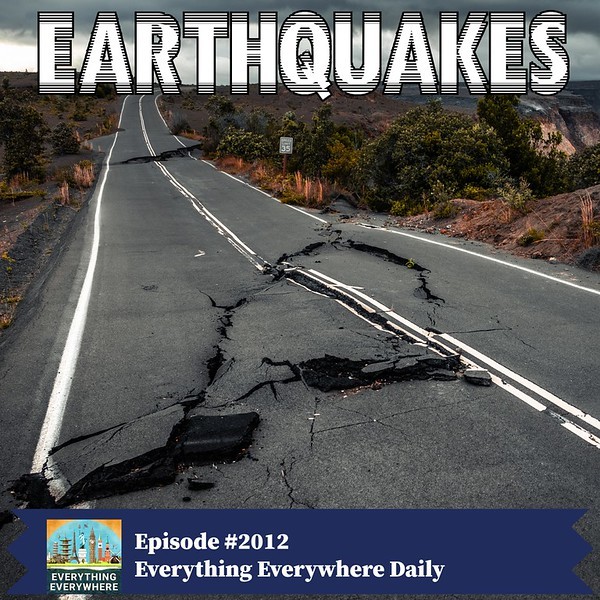

Earthquakes are a constant reality on our planet, occurring roughly 20,000 times per year. While most go unnoticed, their potential for destruction makes them among the most feared natural disasters. This overview explains what causes earthquakes, how they’re measured, and where they strike most frequently.

The Science Behind the Shake

Before the theory of plate tectonics, earthquakes were often attributed to mythology or outdated geological models. Today, we know that earthquakes result from the movement of Earth’s tectonic plates. These massive plates slowly shift, collide, or slide against each other at boundaries called fault lines. When pressure builds up along these faults, sudden slips release energy in the form of seismic waves.

These waves come in four primary types:

- P-waves (Primary) : The fastest, traveling through solids, liquids, and gases.

- S-waves (Secondary) : Slower, and can only move through solids.

- Love waves : Side-to-side motion, often the most destructive to infrastructure.

- Rayleigh waves : Rolling motion, similar to ocean waves, and can cause significant damage.

Types of Earthquakes

Earthquakes aren’t all the same. They are categorized into four main types:

- Tectonic : The most common, caused by plate movement at fault lines. Convergent boundaries (where plates collide) create subduction zones, leading to volcanoes and earthquakes. Divergent boundaries (where plates separate) cause shallower earthquakes. Transform boundaries (where plates slide past each other) generate high-friction quakes.

- Volcanic : Triggered by volcanic activity, these are typically smaller but can occur alongside eruptions.

- Collapse : Caused by underground structures failing, such as sinkholes or caves.

- Explosion : Man-made, often from mining or blasts. These can mimic natural earthquakes in power.

Measuring the Magnitude

The scale we use to measure earthquakes is often mislabeled as the “Richter Scale,” but the modern standard is the Moment Magnitude Scale. This system accounts for different types of seismic waves, providing a more accurate assessment of energy released. The scale is logarithmic, meaning each whole number increase represents roughly 32 times more energy. For example, a magnitude 7 earthquake releases about 1,000 times more energy than a magnitude 5 quake.

The most powerful earthquake ever recorded was a 9.5 magnitude quake in Chile in 1960.

Earthquake Hotspots

The vast majority of earthquakes occur in two primary regions:

- The Pacific Ring of Fire : A horseshoe-shaped zone where many tectonic plates converge, causing frequent volcanic and seismic activity. The San Andreas Fault in California is one of the most active areas within this region.

- The Alpide Belt : Extending from Europe to Asia, this zone is also a hotbed for earthquakes due to the collision of tectonic plates.

Beyond the Numbers

The destructive potential of an earthquake depends not only on its magnitude but also on location, infrastructure, and geological conditions. A large quake in a sparsely populated area may go unnoticed, while a smaller quake in a densely populated region with poor construction can be devastating. The 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan, for example, shifted parts of the seafloor by over 50 meters.

Earthquakes are a daily occurrence, not just headline-grabbing disasters. The Earth is a dynamic planet, and its constant movement means shaking is inevitable.