The aftermath of World War II demanded accountability for the horrific atrocities committed by the Axis powers. While punishing every individual involved was impossible, the Allied forces decided to prosecute key leaders to deliver some measure of justice. This led to the Tokyo Trials, a controversial but necessary attempt to address the scale of war crimes committed by Imperial Japan.

The Scale of Atrocities in the Pacific

World War II remains the deadliest conflict in human history, claiming tens of millions of lives. The brutality was particularly acute in the Pacific Theater, where the Empire of Japan engaged in systematic violence, including mass murder, torture, and rape.

Some of the most notorious incidents include the Rape of Nanking in 1937, where Japanese soldiers murdered hundreds of thousands of civilians and systematically raped tens of thousands of women. The Bataan Death March saw 78,000 prisoners forced to march 66 miles in horrific conditions, resulting in the deaths of thousands due to starvation, brutality, and execution. The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, launched without a declaration of war, was another violation of international norms.

These events, among countless others, created a moral imperative for the Allies to hold Japanese leaders accountable.

Establishing the Tokyo Tribunal

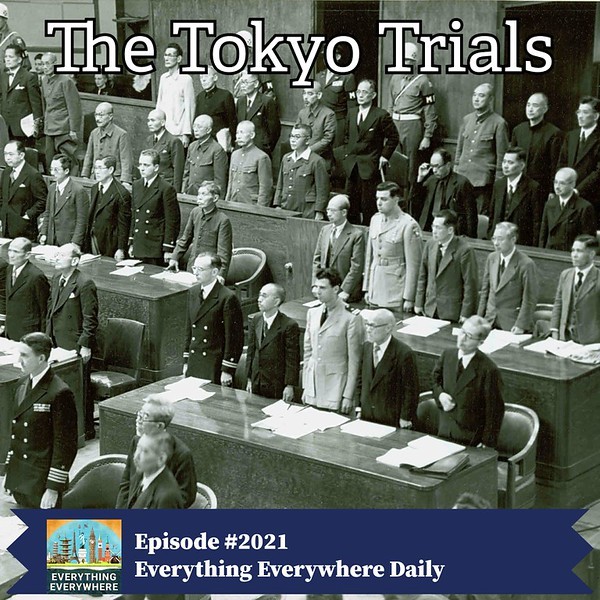

The Allies decided to focus on high-ranking political and military officials, creating the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) under the authority of U.S. General Douglas MacArthur. The IMTFE brought together judges from 11 Allied nations, including the United States, Australia, China, France, India, the Netherlands, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain.

The trials were based on three categories of charges:

- Class A: Crimes against peace (waging aggressive war).

- Class B: Traditional war crimes (violations of the laws of war).

- Class C: Crimes against humanity (systematic violence, enslavement, etc.).

To facilitate prosecution, new charges were created specifically for these trials, mirroring the Nuremberg proceedings against Nazi leaders. The court allowed a wide range of evidence, including unsigned documents, and applied a strict “best evidence rule” requiring originals to be presented.

Key Defendants and the Trial Process

Twenty-eight high-ranking Japanese officials were put on trial, including former Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, Foreign Minister Koki Hirota, and General Iwane Matsui, who was linked to the Nanjing Massacre. The prosecution argued for command responsibility, holding leaders accountable for the actions of their subordinates. To secure a conviction, the court required proof that the crimes were widespread, the defendant knew about them, and they had the power to stop them but failed to do so.

The trial lasted nearly two years, with the prosecution’s case taking 192 days and the defense responding over 225 days. The defense argued that the charges were vague, that the laws did not exist at the time of the offenses, and that states—not individuals—should bear responsibility for war crimes. They also pointed to Allied war crimes as a counterargument.

Dissent and Controversy

The court delivered its verdict after fifteen months, finding all but one defendant guilty. Seven were sentenced to death, including Tojo, Hirota, and Matsui. However, the proceedings were deeply controversial, with five of the eleven judges filing dissenting opinions.

Some argued that Emperor Hirohito should have been tried, citing evidence of his direct involvement in the war effort. Others criticized the trial as biased, conducted by the victors with little regard for fairness. An Indian judge went so far as to call it “victor’s justice,” arguing that the accused were punished simply for losing the war.

Legacy of the Tokyo Trials

Despite the controversies, the Tokyo Trials established a crucial precedent: national leaders could be held personally accountable for war crimes under international law. The trials affirmed the illegality of aggressive war, the rejection of “just following orders” as a defense, and the principle of individual criminal responsibility.

Following the main trial, over 5,700 lower-ranking personnel faced prosecution for crimes like medical experimentation, rape, torture, and extrajudicial executions. The proceedings remain a landmark in international law, shaping modern standards for war crimes tribunals and accountability.